In war mythology, the parade ground is considered hallowed ground. It is thought to be the place where ghosts of soldiers past go back to visit their mates.

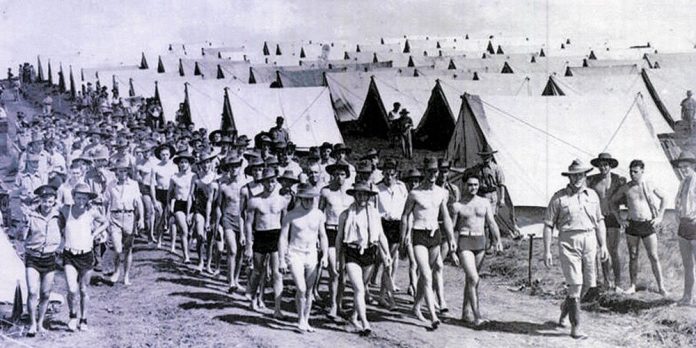

Between 1939 to 1945, it is estimated that 20,000 to 30,000 soldiers stood on the white sand of Kings Beach, Caloundra, to farewell Australia and join the overseas war effort.

Caloundra RSL War Museum curator Mr Trevor Smith OAM has photos of the young men and women (including the one pictured above), whose last memories of their home before they hit the horrors of war may have been the scent of salt entering their nostrils, the sound of crashing waves and the magnificent beauty of a Southeast Queensland coastline.

This is one of the reasons Gary Phillips, Caloundra sub-branch welfare officer, wished to see a life-size bronze statue of a soldier, nurse and wounded soldier on a single plinth at Kings Beach.

Together with this, Mr Phillips believes it will add to the knowledge of Caloundra’s role during the war years.

“It is our heritage,” he says.

Keep local news coming by subscribing to our FREE once-daily news bulletin. Simply plug in your email at the top of this article

Mr Phillips says his interest was piqued at Caloundra’s commemoration of the 70th anniversary of Victory in the Pacific, when he met various people who related their story to him.

One of them was Mary Tutt (wife of Sunshine coast historian Stan Tutt) and the other, Nev Anning. Over time, Mr Phillips developed a friendship with Mr Anning that included relating adventures that could hardly happen in the 21st century.

“He said he and a mate decided they were joining up, when a third person heard, he wanted to join them.

“However, he owned and ran a dairy farm and therefore was part of the essential services.

“Not to be stopped there, they built a house, so he could get a manager and go to war with them.”

Later on, he and Nev Anning were captured and became Changi prisoners of war.

Mr Phillips is mindful of the various plaques already in place and he mentions the Caloundra Fishing Club jetty.

“That’s where soldiers would leave to go to Bribie Island and patrol,” he says.

Additionally, there is the War Memorial Walk (Kings Beach to Wickham Place) where, already, there are 2000 plaques laid.

Mr Phillips says that if a plaque is to be laid for a person from another country, permission must be granted.

“Since email, gaining permission is much easier,” Mr Phillips says, noting that previously, with snail mail it was a much longer process.

Stay up-to-date, follow Sunshine Coast News on Facebook

Mr Phillips says he was able to progress the idea of a bronze statue with support from the RSL Sub-Branch president Ms Heather Christie, councillor Terry Landsberg along with Caloundra RSL War Museum curator, Trevor Smith.

However, it would take about $300,000 to create the piece and while Mr Phillips was busy calling for donors and checking out available government grants, just two weeks ago he received a wonderful surprise.

“A Coast philanthropist has stepped forward and committed to a $300,000 building donation.”

The sculptors chosen to carry out this work were Mark Snell and Jane Bailey, of Lavaworx Art Studio at Coolum. Mr Snell created the ANZAC Centenary Memorial, at Freedom Park, Pialba, Hervey Bay, and Mr Snell and Ms Bailey combined to create the artwork for the Gallipoli to Armistice Memorial in Maryborough.

At this location, the sculpture includes two black granite walls depicting a World War 1 trench. The Light Horsemen bronze statue represents a brave ANZAC jumping over that trench on his way to battle.

Now that the project is funded, Mr Phillips is putting timelines into place for construction.

Caloundra in WWII

Articles on the Sunshine Coast Council website refer to the role of Caloundra during WWII. On the website heritage.sunshinecoast.qld.gov.au (under ‘Caloundra’) one article notes: ‘In the war years from 1939 to 1945, Caloundra was classified as a restricted area by the Australian Defence Force. Many homes were commandeered by the Armed Forces and the Caloundra School in Queen Street became the headquarters for the American Army, and later the Australian Coast Artillery.’ An extract from another article in the council’s ‘Backward Glance’ series states: “With troop trains passing through, soldier camps, MPs stationed at the main intersection on what was known as ‘Fiveways’ Landsborough, the Bribie Island Fortifications and Military Jetty at Golden Beach and restricted zones such as Caloundra, almost all of the Sunshine Coast region was involved in some way, including its residents.

Did you know?

Caloundra was also the site of a radar training school as well as a number of signal stations. Caloundra was chosen for its close proximity to the shipping channel and was used as an observation area for shipping movements. Many of the local houses were commandeered to house service personnel. There were a number of gun emplacements along the headland, as well as boats and jetties to service the Fort Bribie emplacements and personnel. Artillery practice and other army training was held in the areas of Battery Hill and Currimundi.

History of the ANZAC day dawn service

The following text is from the Australian War Memorial website:

The Dawn Service observed on Anzac Day has its origins in an operational routine which is still observed by the Australian Army today. The half-light of dawn plays tricks with soldiers’ eyes and from the earliest times the half-hour or so before dawn, with all its grey, misty shadows, became one of the most favoured times for an attack. Soldiers in defensive positions were therefore woken up in the dark, before dawn, so that by the time the first dull grey light crept across the battlefield they were awake, alert and manning their weapons. This was, and still is, known as ‘Stand-to’. It was also repeated at sunset.

After the First World War, returned soldiers sought the comradeship they felt in those quiet, peaceful moments before dawn. With symbolic links to the dawn landing at Gallipoli, a dawn stand-to or dawn ceremony became a common form of Anzac Day remembrance during the 1920s; the first official dawn service was held at the Sydney Cenotaph in 1927. Dawn services were originally very simple and followed the operational ritual; in many cases they were restricted to veterans only. The daytime ceremony was for families and other well-wishers, the dawn service was for old soldiers to remember and reflect among the comrades with whom they shared a special bond. Before dawn the gathered veterans would be ordered to ‘stand to’ and two minutes of silence would follow. At the end of this time a lone bugler would play the Last Post and then concluded the service with Reveille. In more recent times, families and young people have been encouraged to take part in dawn services, and services in Australian capital cities have seen some of the largest turnouts ever. Reflecting this change, the ceremonies have become more elaborate, incorporating hymns, readings, pipers and rifle volleys. Others, though, have retained the simple format of the dawn stand-to, familiar to so many soldiers.