Indigenous loggers from the 1920s are among those ignored by the pages of history, a University of the Sunshine Coast researcher has found.

Rose Barrowcliffe spent three years researching to uncover the missing chapters of history from K’gari (Fraser Island).

In honour of her remarkable efforts, the proud Butchulla woman was appointed by the Queensland Government as the inaugural First Nations Archive Advisor at the Queensland State Archives (QSA).

The role at the QSA was created as a part of the Queensland Government’s Pathway to Treaty commitment, recognising her research publications that highlighted the gaps in narratives by and about Indigenous peoples.

It was a curiosity in her own family history that led her to explore the USC’s K’gari Research Archive (KRA) and sparked a post-graduate PhD study.

Her work resulted in a discovery that much of the region’s Indigenous past had been shelved away, including that of Indigenous loggers from the 1920s, and even family stories of her great grandmother.

“The most significant story that I uncovered was one that shed light on my great grandmother’s life and the story of why she ended up being removed to a mission,” she told Sunshine Coast News.

“It’s a point at which the history of my whole family changed.

“She was removed to Barambah Mission, now known as Cherbourg, and she never made it back to the island.

“My grandmother and mother were born on Cherbourg Mission as well.”

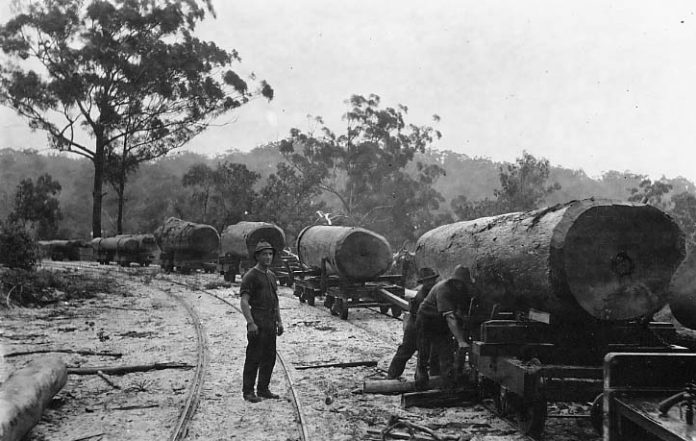

“The other stories that I found interesting were of the Aboriginal and Butchulla people who worked in the logging industry on K’gari.

“We often only hear about the white people that lived there, but Butchulla people were involved in every part and every stage of the island’s history.

“I also liked learning more about the general history of the island. Stories like a ship running aground offshore and spilling its cargo of kegs of beer. The islanders had a big party that night!”

Raised east of Gympie, Ms Barrowcliffe left the region after high school and spent 18 years overseas before returning in 2017.

Despite the many changes in that time, including Butchulla people being granted native title over K’gari, she was surprised to find the lack of information on the traditional history of the island.

“I had expected it to have Butchulla stories and perspectives in there, but the reality is that there are very few records in that archive that were created by Butchulla people, or represent their perspectives, or even contain information them.

Help keep independent and fair news coming by subscribing to our free daily news feed. All it requires is your name and email. See SUBSCRIBE at the top of this article

“That’s what sparked my interest in archives. I became very interested in how the process of record-keeping affects what we come to know as history.”

Ms Barrowcliffe said uncovering the information left her with a sense of surprise and an overwhelming feeling to want to protect and preserve the history.

“Aside from my great grandmother’s story the thing that surprised me was my reaction to the archive over time.

“I became quite protective of some of the people mentioned in the records and I found it upsetting that, so often, the Aboriginal and Butchulla people were simply mentioned to by a first name or nickname and that’s it. No details about their family or what their day-to-day life was like.

“It stands in stark contrast to the detail in the stories about early colonists.

“It’s upsetting because it gives the impression that the Aboriginal people weren’t important.”

Ms Barrowcliffe said while the history and archives did not always represent traditional or Indigenous history, every finding, not matter how small, remained relevant in piecing together the puzzle.

“Firstly, it’s important to realise that any archive about our Traditional Country is relevant to us.

“Secondly, we need to stop equating frequency with relevance. There are records in the archive that mention a Butchulla person just once in the record, but that is still significant because it means we can pinpoint them to that time and place in history.

“That is particularly important for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities that have been impacted by Stolen Generations.

“Sometimes a single mention in one record is enough to connect them to the bigger story of their family and community.”

Her research process involved hours of reading and transcribing archival documents, in some cases crowdsourcing volunteers to help with the mammoth task.

As part of her unique role at the Queensland State Archives, Ms Barrowcliffe will be assisting QSA staff to identify ways that records in their care can assist in preserving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories in their vital role in the history of Queensland.

Her significant work is now opening the door to change perceptions and segregation of Indigenous history and non-Indigenous history.

“It’s so common for ‘Australian history’ to be told as if it starts from the arrival of Cook, and only involving the stories of colonists.

“But that is a very myopic view of this nation and we need to foster a history that is inclusive of everyone’s stories.

“Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were here long before colonisation and have been present at every stage in our history, which needs to be reflected in our historical narratives.”

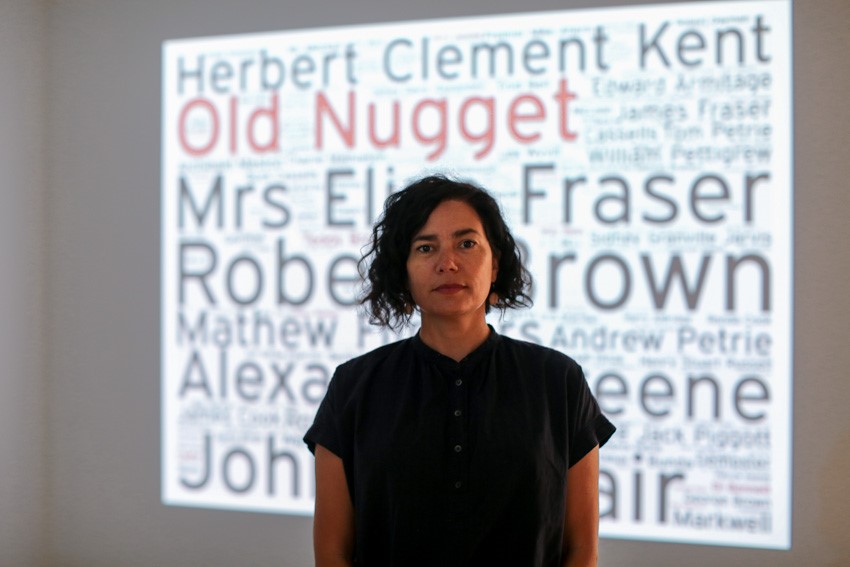

Ms Barrowcliffe’s findings are being presented as part of a virtual exhibition, Reading between the lines: Uncovering Butchulla history in the K’gari research archive, at the USC Gallery until October 30.

“The exhibition is a series of seven mini-documentaries that take visitors on a virtual tour of Butchulla Country and invite them to hear the perspectives and stories of Butchulla community members about the K’gari Research Archive and archives in general.

“The exhibition challenges visitors to consider who is present and who is absent in any historical narrative they hear.”

Fraser Island timber industry:

In 1918, NSW timber merchant Mr H. McKenzie, of Sydney, bought the rights to log 4000 hectares of land on Fraser Island for 10 years and immediately began building the first and only timber mill on Fraser Island at the McKenzie’s Jetty site, just south of Kingfisher Bay Resort and Village. McKenzie Ltd. was responsible for this mill,a jetty and a number of steam locomotives.

In 1920 the Forestry Camp was moved from the mouth of Wanggoolba Creek to Central Station where a busy community developed, with forestry workers living in tents, bark huts and houses. Vegetable gardens and fruit trees were planted,

a school was built for the children and machinery sheds, stables and plant nurseries were established.

Prior to 1925, satinay trees had not been popular as they were regarded as too

soft for hardwood and too hard for softwood. But the timber was found to be

resistant to white ant, borer and fire, became popular for cabinet making.