A relatively unknown fragment of the Sunshine Coast’s past has been unearthed in the Pumicestone Passage following the Bribie washover.

Several 130-year-old oyster beds have been exposed by shifting sands following the tidal breakthrough earlier this year, revealing a fascinating slice of local history.

Photographer Doug Bazley, of Blueys Photography, captured some stunning images of the beds recently.

“I noticed some objects in the sand, south of the TS Onslow Naval Cadets (Golden Beach), so I let the bird (drone) go to check it out and it was interesting to see quite a few oyster beds exposed from times long gone,” he said via social media.

Local historian and author John Groves said it had probably been about 70 years since the beds were so obvious.

“Most of the time they have been under water,” he said. “But the tide has moved the sand around the northern end of the passage so they are exposed now.”

The passage has experienced dramatic change since the breakthrough, including a bridge of sand across the waterway and an expanse of sand at Happy Valley.

The exposed beds are a marker of the region’s once thriving oyster farming industry dating back to the late 1800s.

There were several successful leases, particularly from the 1890s to the 1930s.

Mr Groves said that “they were a big business.” During its peak, the industry involved hundreds of people and docks were built all along the passage.

“Tom Maloney farmed them on sticks against Bribie, while there was a big lease at Lamerough Creek and there was one near the (Caloundra) Power Boat Club, along with others,” said Mr Groves.

He said the Moreton Bay Oyster Company was a big player during the heyday of oyster farming in the passage but it inadvertently played a role in ending the boom.

“They asked the John Burke Shipping Company to bring some fan shells here, to grow oysters on them,” he said.

“But there were mud worms in the fan shells and they ruined the oysters in the passage and in Moreton Bay.”

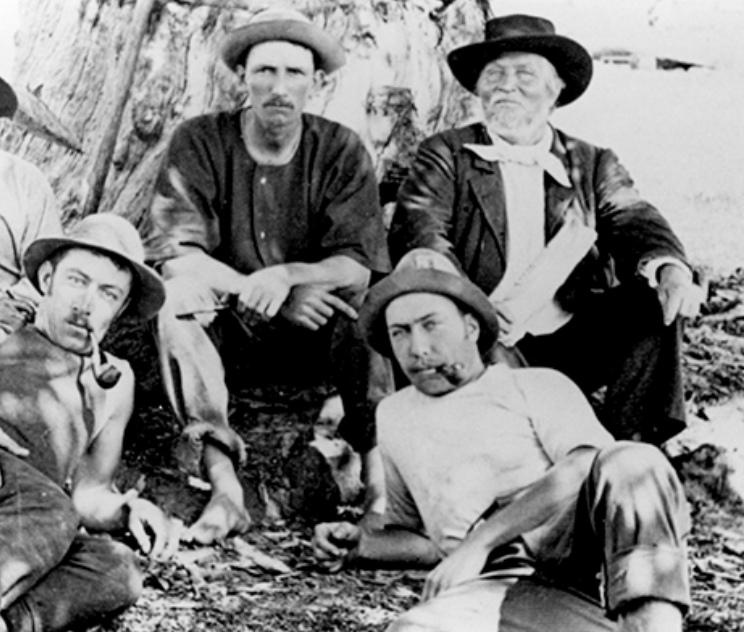

The ‘Oyster King’ James Clark owned more than 30 dredging sections and employed more than 25 families.

Four generations of the Tripcony family were involved in oyster farming.

Tom Tripcony, 70, said his descendants thrived in the passage at the turn of the century.

“Oysters were prolific,” he said.

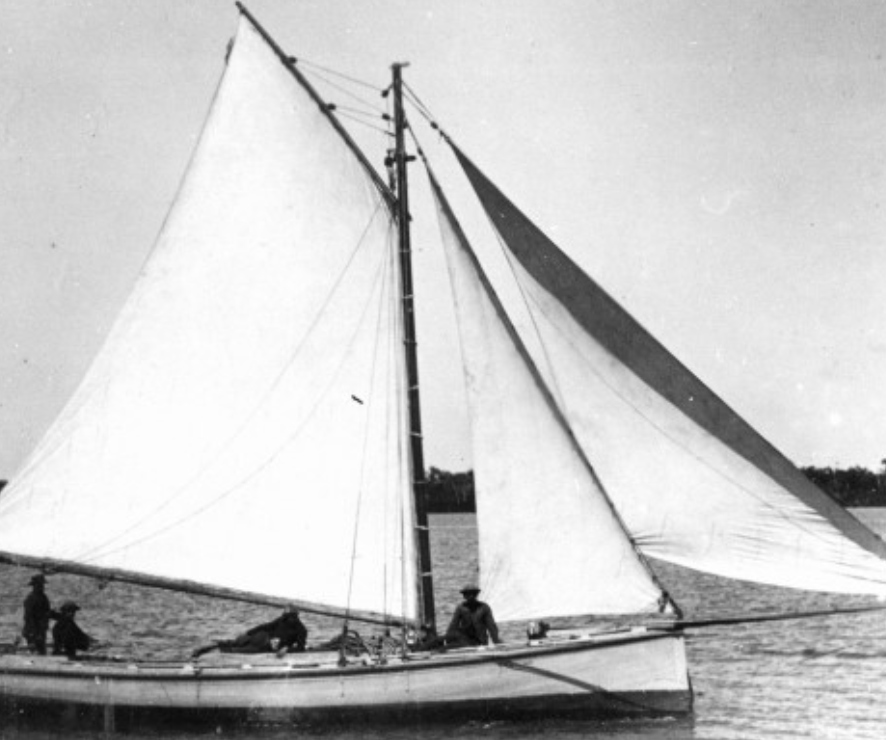

“They were everywhere and they were raked up with a big rake behind a boat.”

“I’ve seen photos of piles of oysters as big as a house.”

“And the water used to be incredibly clear when there were lots of oysters around.”

“It (oyster farming) was huge.

“It was one of the bigger industries around, when there weren’t many industries at all.”

Mr Tripcony said many oysters were shipped to Sydney, while many weren’t even farmed for food.

“They didn’t eat them,” he said.

“They used to burn them and turn them into lime. It was two shillings a bag for burnt oyster lime, which would be turned into concrete.”

Mr Tripcony believed his family had been involved in oyster farming from the 14th century.

They moved from Cornwall in England to Australia and briefly attempted gold prospecting in Victoria before resuming oyster farming in Queensland.

They settled on land, to be known as Cowie Bank, between Hussey and Glasshouse Mountain Creek, about 20km east of Beerburrum.

Thomas Tripcony Senior and his sons, Andrew, Con and Thomas were heavily involved in the industry. They dredged the oysters with a wire mesh rake pulled behind a flat-bottomed punt.

Mr Tripcony’s great, great grandfather was Andrew, who owned Caloundra’s first store in 1910.

“If you go to Cowie Bank now you can still see the old bricks, which I think the family got by swapping for oysters,” he said.

Since the mud worm infestation in the 1930s, there has been limited oyster farming in the passage.

Help keep independent and fair Sunshine Coast news coming by subscribing to our free daily news feed. All it requires is your name and email. See SUBSCRIBE at the top of this article.

Mr Tripcony farmed oysters, mainly in Ningi Creek near Toorbul during the 1980s.

“We had a few leases there but a prawn farmer put antibiotics in the water and killed off the oysters,” he said.

“We had the one (lease) at Cowie Bank too but the water wasn’t fresh enough there, then.”

QX Disease, which is believed to be a result of poor water quality, arrived in the 1970s and contributed to the lower quantity and quality of oysters.

“But people still do farm oysters (in the passage),” Mr Tripcony said.

“They’re trying to re-populate the passage at the moment, putting in cages of oyster shells to create more oysters and clean the water.”