A freshwater crayfish native to the Sunshine Coast hinterland is on the brink.

The Conondale spiny crayfish was added to the threatened species list for the first time earlier this month.

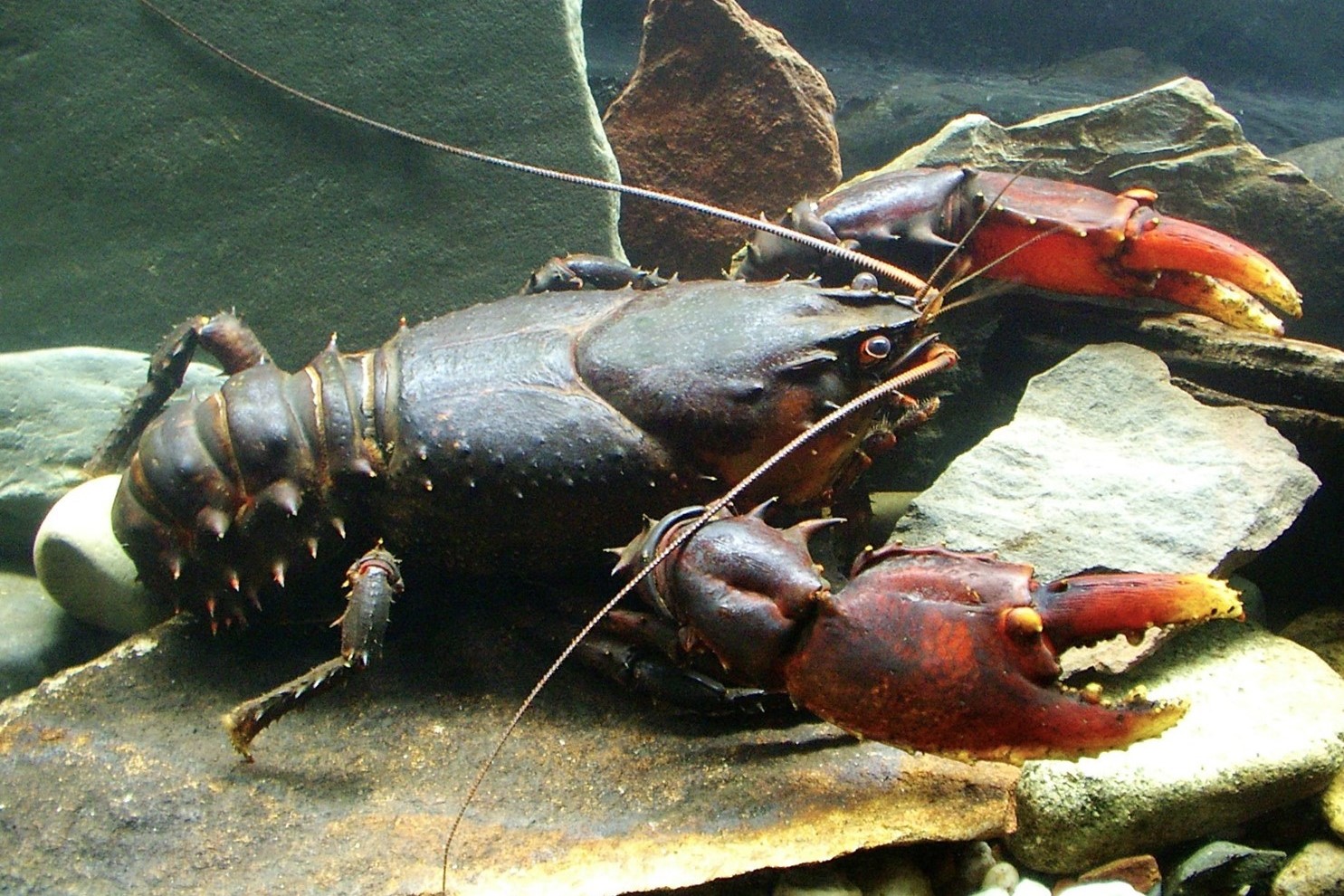

Known for its distinctive exoskeleton, the relatively large crayfish is only found within the Conondale and Blackall ranges, and the Bellthorpe Mountains that link them.

University of the Sunshine Coast PhD student Grace Smith said it was an “amazing” creature with some quirky characteristics.

“The Conondale spiny crayfish is Queensland’s largest freshwater invertebrate, living for over 50 years, growing up to 2kg and only reaching reproductive maturity after 12 years,” she said.

“They live in huge burrows in the creek beds, which we think may be passed down through generations, potentially making these burrows hundreds or even thousands of years old.

“As adults, they are apex predators with a very intimidating hiss and spine-covered shell.

“Early settlers reportedly shot one at first sight when they were discovered.”

But she said there was only limited information about them.

“Very little research has been done on this species,” she said.

“But we know that recently their numbers have dropped drastically, mostly as a result of habitat degradation, invasive species like pigs and poaching.”

Twenty species around Australia were added to the threatened list for the first time.

UniSC special research project student Ollie Scully said Conondale spiny crayfish (Euastacus hystricosus) once thrived.

“They are now very rare but they would’ve once lived all through places like Obi Obi Creek,” he said.

He was unsure how many could be left.

“There hasn’t been a lot of work published on population dynamics and it can be hard to predict with crayfish, as their moult cycle makes it difficult to use mark and recapture methods,” he said.

Do you have an opinion to share? Submit a Letter to the Editor at Sunshine Coast News via news@sunshinecoastnews.com.au. You must include your name and suburb.

“We do know that large individuals have become increasingly rare.

“You’d be lucky to find more than three large crays along a 1km stretch of creek, even in good spots for them, though this is partially because they’re secretive.”

He said land clearing and degradation of riparian (streamside) habitat would have contributed to their decline on the Blackall Range.

“They are also very slow growing so, unlike normal yabbies, if you take just a few from the creek it can really knock the breeding population around,” he said.

Ms Smith outlined how people can help the species survive.

“The best things we can do for their conservation is protect their habitat by controlling weeds, managing pests, and restoring native vegetation, and on an individual level, raise awareness and respect to help curb illegal or accidental collection,” she said.