Though the official vote won’t happen until next month, Brisbane has already unofficially been awarded the hosting of the 2032 Summer Olympics.

This is potentially a great opportunity for Brisbane, Queensland and Australia. It will also be a catalyst to speed up long-term planning agendas for the fast-growing South East Queensland (SEQ) region.

In the past, Olympic Games have resulted in soaring budgets — Tokyo’s US$15.4 billion budget being the latest example — and infrastructure that has lain unused after the 16-day event is over. This has led to justified criticism the Olympics are not the jewel in the crown they were once considered.

For many past host cities, the games have not been a boon, but a drag. Greeks, for instance, have questioned how their country benefited from hosting the 2004 Summer Olympics, which left the country in crippling debt and with many venues abandoned and in disrepair. As these photos show, they are hardly the only ones.

So, what will make Brisbane 2032 different?

Temporary venues and a more dispersed games

First, the International Olympic Committee has introduced a more flexible and efficient approach to hosting, which it calls the “new norm”.

In short, this means host cities will need fewer new venues, a smaller athletes’ village and less Olympics-specific infrastructure overall. Temporary, flexible venues will be allowed for the first time, and venues can be shared by multiple sports. Athletes will also fly in just for their competitions and leave when they are over.

This new approach has been key to making Brisbane’s bid affordable. The operating cost for the Brisbane Olympic and Paralympic Games is projected to be a modest A$4.5 billion (US$3.4 billion), which is less than a third of Tokyo’s budget and the US$15 billion final cost of the London 2012 Games and US$13.2 billion cost of the Rio 2016 Games.

Second, the plans for the Brisbane Olympics and Paralympics are strongly grounded in existing development plans for the city.

Unlike host cities in the past, these Olympics will not be the sole reason for new development projects. Instead, they will be the catalyst for bringing forward current infrastructure and urban development plans. Around $400 million in road network improvements and $23 million in transport upgrades, for example, will be fast-tracked thanks to the successful Olympics bid.

Do you have an opinion to share? Submit a Letter to the Editor with your name and suburb at Sunshine Coast News via: news@sunshinecoastnews.com.au

This mirrors the oft-cited “Barcelona model”, based on the Spanish city’s use of the 1992 Olympics to underpin a long-term, city-wide improvement plan. Studies argue such “event-themed” regeneration is linked with more positive legacy outcomes.

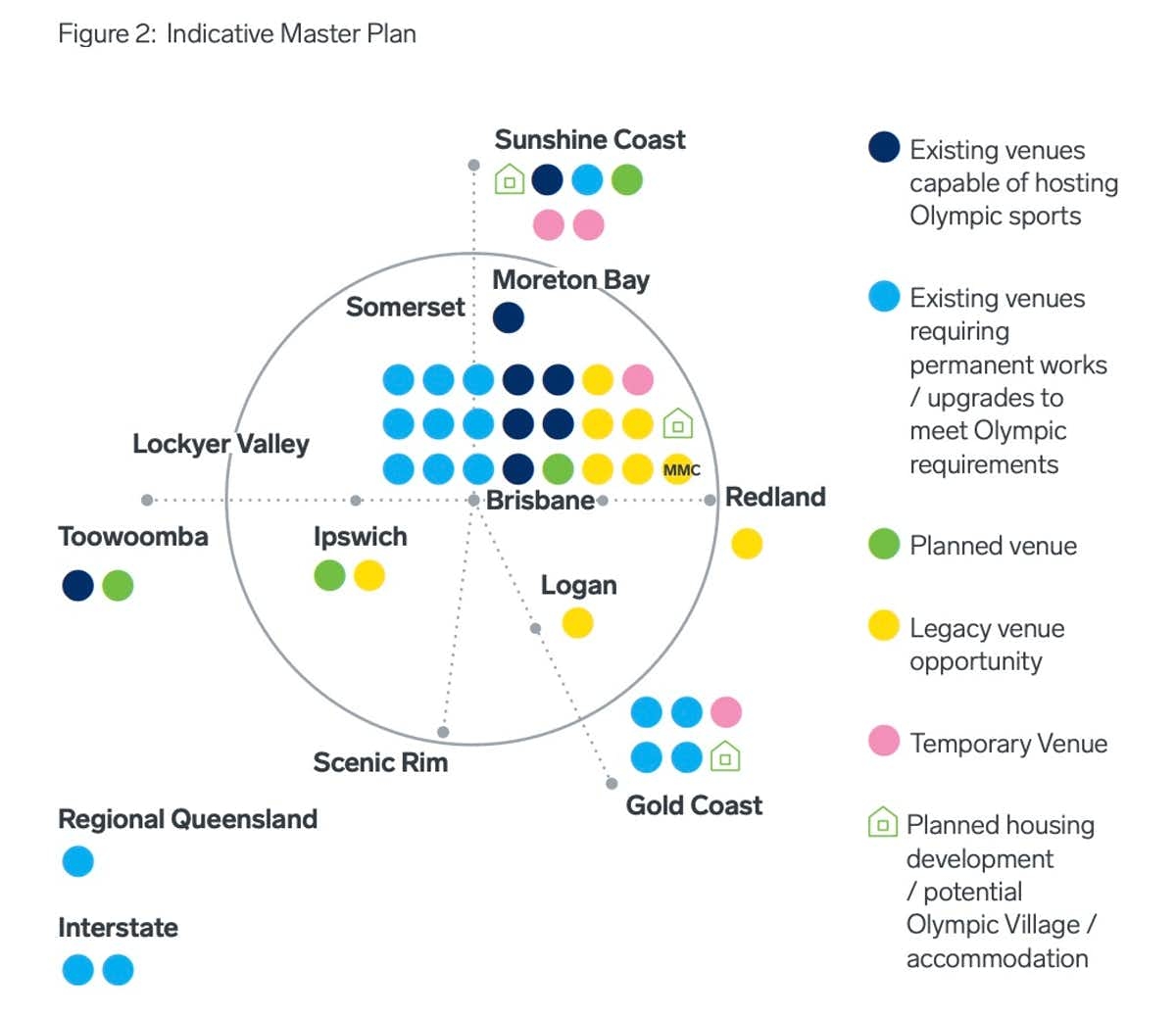

Third, the 2032 Games will be the first to represent a regionally spread-out hub-and-spoke model. This model aims to disperse the benefits of hosting beyond Brisbane, with permanent venues planned across the SEQ region, including the Gold and Sunshine Coasts, Redland Bay, Ipswich, Toowoomba and the Scenic Rim.

The model also includes three proposed Olympic villages to provide easy access to these venues.

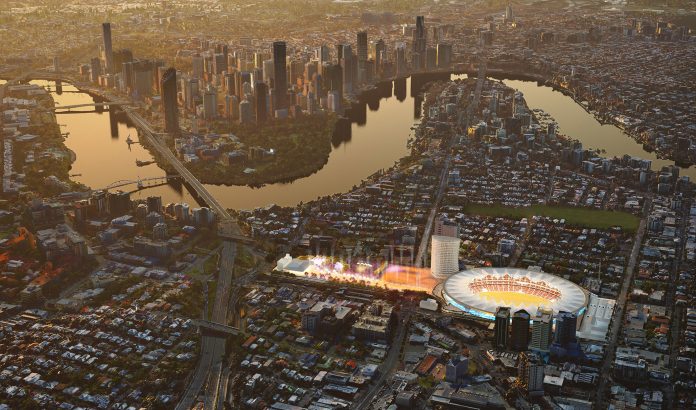

These dispersed venues will be legacy project. An example is the Albion Precinct, where a proposed new stadium could be built to host the athletics in conjunction with existing plans for a food and lifestyle hub. There will also be temporary facilities to host training camps and preliminary events.

One of the main challenges for the Olympic organisers and governments at all levels will be delivering on major, costly transport infrastructure. This will be needed to link the various event sites and transport visitors, athletes and their support crews, and the media without a glitch.

An early feasibility study suggested the hub-and-spoke model would allow for a 45-minute travel region, with every venue within 45 minutes of Brisbane. The current projected costs for the SEQ portion of the rail link are A$5.3 billion (US$4 billion), although the proposal will need some rethinking as it has been rejected by Infrastructure Australia as being too costly.

Long-term social and environmental planning

Lastly, the social and environmental aspects of hosting the Olympics are front and centre of the Brisbane bid. Research by KPMG and The University of Queensland shows a projected economic and social benefit of $17.61 billion for Australia overall and $8.1 billion for Queensland alone.

The “social benefits” are measured in a variety of ways. For residents, the prestige of hosting the games and resulting civic pride should lead to enhanced community spirit. The Olympics can also be used to boost people’s health and well-being by encouraging increased participation in physical activity. This could lead to a lower risk of chronic disease and improved mental health.

Finally, the benefits of volunteering, both for the volunteers themselves and the wider community, are well documented. Volunteer numbers in Australia have been in decline since COVID hit.

Help keep independent and fair Sunshine Coast news coming by subscribing to our free daily news feed. All it requires is your name and email. See SUBSCRIBE at the top of this article

This could be a great way to kick-start a new drive to encourage people to volunteer, although there are questions about whether volunteer participation for such mega-events has long-term benefits.

With regard to the environment, the Olympics are often associated with a large carbon footprint. Brisbane’s bid document, however, highlights long-term measures to reduce waste and pollution. These include Queensland’s plastic pollution reduction plan, as well as the expanded use of public transport to reduce traffic congestion and emissions.

Why legacy planning matters

However, none of this happens without significant advance planning. Intangible legacy planning, such as promoting sports to the public and volunteer participation, needs specific attention and should begin as soon as hosting rights are awarded.

Legacy planning should also come under the remit of a distinct body from the Olympic organising committee. This is needed so that legacy planning is not subsumed by the immediate work of event planning and delivery.

Additionally, the Olympic organising committees typically disband soon after the games and the staff move on to other (often international) events. The legacy body and its budget need to continue to deliver long after the event concludes.

Such a model has yet to be widely adopted by host cities. London 2012 was widely recognised as the first Olympic Games of the so-called “legacy era”. However, it was criticised for leaving its legacy planning too late to be fully effective.

The 2032 Brisbane Games have the opportunity to showcase a new and improved model of Olympic hosting. The new “Brisbane model” for Olympic hosting could be one the IOC and future host cities will praise and seek to replicate.

Authors